By Emmanuel Young, SJIEP Fellow (2022)

William “Bill” Corsey III was about 15 years old when he first learned about his family’s history. He heard that there was a man with the same name as him buried in a Black cemetery in South Jersey. And that year, in 1964, Corsey and his family began searching for the tombstone across the region, from his hometown in Gloucester County down to Atlantic City.

In 1965, they found their ancestors buried at Mt. Zion African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Cemetery in Woolwich Township. Corsey and his relatives are one of two local families who’ve traced their lineage back to the historic burial ground.

The Mount Zion AME Church owns the cemetery, which according to the New Jersey Historic Trust, sits in the historic African American settlement of Small Gloucester. The church—built in 1834 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001—was once a pitstop for enslaved people escaping the South as part of the Underground Railroad. And today, more than two centuries later, it remains a sanctuary and a landmark for those who wish to learn about its history.

Corsey, now 73, recalls that when they found his relatives’ tombstones, the cemetery was overgrown with weeds and littered with garbage. Decades later, he and his cousin Brenda Money, along with another Gloucester resident whose ancestors are buried in the cemetery, began volunteering with the Historical and Educational Lodge-Hall Preservatory Inc (H.E.L.P. Inc.). They take care of the site by occasionally cutting the grass and doing some groundskeeping.

Eventually, Corsey, a former teacher, became a member of H.E.L.P. Inc. as a tour guide. The 501(c)3 was founded in 1998 to promote the history of Mt. Zion AME Church, Mt. Zion Cemetery, and the Richard Ave. School in Swedesboro. Corsey supports their efforts by hosting tours of the church and the gravesite and telling the story of the church and his family.

Corsey gives visitors the backstory of finding his ancestors’ tombstones at the cemetery, where thirteen Black soldiers from the Civil War are also buried, among some 200 unmarked graves. He tells them how he traced his roots by working with historians over the last few decades. Corsey has since located dozens of death, birth, and marriage certificates dating back to 1810, including photos of family members he’s yet to identify.

Piecing together his family history, Corsey learned that his great-grandfather, William Corsey Sr., born in 1810, was enslaved in Oxford, Maryland. Before 1845, he escaped from Maryland and went north to Swedesboro, New Jersey.

Corsey Sr. would soon meet his future wife, Lydia Farmer, a Native American who had assimilated into the local population. The two would go on to have more than 13 children and build a new life in New Jersey in the Black community of Gloucester County.

“It’s funny, really,” he said. “When I look at his picture, I see me in him. Same complexion and all.” For Corsey, the ability to track these photos among Oxford, Maryland’s records and visit his ancestors’ resting place is essential. So is the work of educating the next generation of people about their history and the deep roots of Gloucester’s African American history.

“He is an amazing asset to H.E.L.P.,” said Rev. Sherry Hall, director of programs. It’s one thing for a tour guide to tell its history, but it’s another to have someone whose family is tied to the history of the site tell its story, and we’re ecstatic to have him as a member of our organization.”

Sometimes when he gives the tour to local students and teachers, Corsey says they are upset that there is all this history so close to their schools, yet they never knew about it. And he feels there’s still more to do – so much more history to share with his community and new generations.

“Unfortunately, we do not have a “local history” elective for our students, but we should, said Dr. James J. Lavender, Superintendent of Schools for the Kingsway Regional and South Harrison Township Elementary School Districts. He said the district sends its middle school students over to Mt. Zion Church throughout the year.

He adds, “we never miss the opportunity to stop in front of Mt. Zion Church and highlight the critical role this small building played as a stop on the Underground Railroad or drive by the Richardson Ave. School, which is the last all-black school to be desegregated in NJ, in addition to a number of spots that served key roles during the American Revolution.”

“I hope we can uncover the descendants of the others buried at the cemetery,” said Corsey. “It just tells that the story is not done yet,” he said. “There’s still more to unearth and more to dig up, and we’re not ready to put it to rest and say our final goodbyes to this story,” said Corsey.”

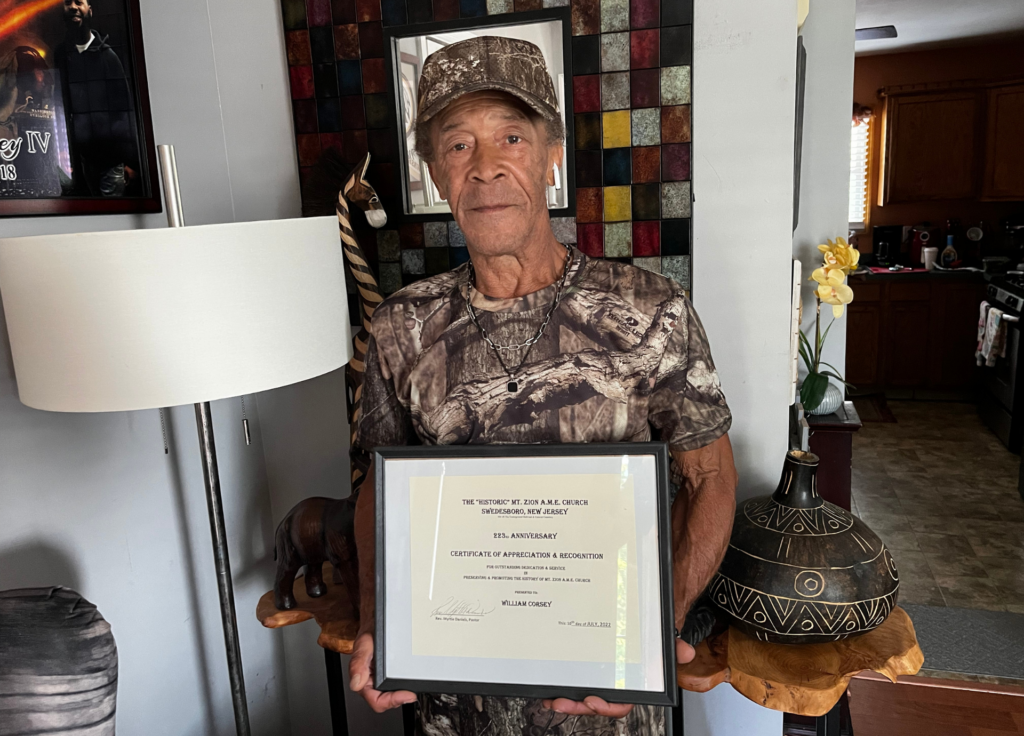

Feature image: William “Bill” Corsey III stands in front of his ancestors’ graves at Mt. Zion AME Cemetery in Woolwich and sketches their tombstones in his notebook on July 3, 2022. (Photo credit: Emmanuel Young)